Gallery Page (Display Only)

Description

Signed with gold inlay, early edo period (keian era, 1648~1652)

NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon & NTHK-NPO Certificates

Swordsmith: Echizen Ju Sagami no Kami Fujiwara Kunitsuna (Shodai – first generation)

Location: Echizen province

Title: Sagami no Kami (Lord of Sagami province)

Clan: Fujiwara

Type of Steel: Jigane oroshi kore o utsu

Gold inlay (test):

- ????????????????

- Tameshiba keijin-giri o motte tachi-kesa oyobi sune kyo fugen Sen’a

- “Sen’a tested this blade on a criminal and cut through a body via the standing kesa [diagonal across the body] cut and with ease down to the [height of the] shin.”

Measurements: Nagasa / Length: 76.2cm (ubu); Sori / Curvature: 1.97cm; Motohaba / Width: 3.0cm

Jihada: Dark jigane with a mix of itame-hada with masame-hada and shirake utsuri

Hamon: Notare and ko-gunome based on suguha with teeth-like ashi

Certificate #1: NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon (a sword Especially Worthy of Conservation)

Certificates #2-4: NTHK-NPO Kanteisho (tsuba, fuchi-kashira and koshirae designated

Authentic) Shirasaya, Edo koshirae, bags

Translation

left to right translation of nakago (Omote – Ura):

omote side: Echizen-j? Sagami no Kami Fujiwara Kunitsuna (??????????)

“Sagami no Kami Fujiwara Kunitsuna, resident of Echizen [province]”

–

ura side: Jigane oroshi kore o utsu (?????)

“Made by using oroshigane steel.”

Gold inlay (test):

????????????????

Tameshiba keijin-giri o motte tachi-kesa oyobi sune kyo fugen Sen’a

“Sen’a tested this blade on a criminal and cut through a body via the standing

kesa [diagonal across the body] cut and with ease down to the [height of the] shin.”

Article

A VERY SPECIAL SHIMOSAKA KUNITSUNA BLADE WITH A VERY RARE CUTTING TEST

First of all, the signature of the blade should be introduced, which reads:

omote side: Echizen-j? Sagami no Kami Fujiwara Kunitsuna (??????????) “Sagami no Kami Fujiwara Kunitsuna, resident of Echizen [p rovince]”

ura side: Jigane oroshi kore o utsu (?????) “Made by using oroshigane steel.”

Kunitsuna, and we are talking here about the first generation of this lineage, was a smith of the Echizen-based Shimosaka School who was primarily active around Keian (??, 1648-1652), although he later also went to Edo to work from there for a certain period of time. His first name was Taemon (???) and he had studied with the local master Kanetane I (??, 1570-1637) and both he and his master are listed as wazamono. That is, the Yamada family of sword tester compiled at the very end of the 18th century a list of swordsmiths ranked on the basis of the sharpness of their blades, a list that was updated and supplemented throughout the early 19th century. This list became famous as the “list of wazamono” and classifies the swordsmiths into the levels saij?-?-wazamono (?????, “supreme sharpness”), ?-wazamono (???, “great sharpness”), yoki/ry?-wazamono (???, “good sharp swords”), and wazamono (??, “sharp swords”). The criteria of wazamono list were as follows: When eight or nine blades out of ten from a certain smith cut with ease centrally through the thorax, the smith was ranked saij?-?-wazamono, for seven to eight ?-wazamono, for five to seven yoki/ry?-wazamono, and for two to four out of ten wazamono. In short, Kunitsuna’s As stated above, the ura side of the tang is signed with the supplement that Kunitsuna had used oroshigane for making this blade. In a nutshell, oroshigane basically has two meanings: One is the smith just refining the tamahagane steel he has received from the tatara furnace that he is going to use for certain parts of the blade, and the other is the smith making the steel for the sword himself, from scratch, i.e. he is making his own tamahagane for which he may use for example steel from old nails, old swords, or old castle gate fittings. So when we read oroshigane in a signature, it means that the smiths wants to stress that he paid special attention to the steel he used for that blade.

The gold-inlay cutting test of this blade deserves special attention, on the one hand because it is rare, and on the other hand because I think the NBTHK erred on the side of caution in quoting it in the Tokubetsu Hozon certificate they issued. Let me address the second point first. On the certificate in question, the cutting test inscription is quoted as follows:

??????????? ????

Tameshiba fuki keijin-giri tachi-kesa oyobi waki-? fukan Sen’a

“Sen’a tested this blade on a criminal and cut through a body via the standing kesa [diagonal across the body] and the waki-? [horizontally across the chest] cuts.”

As you can see, the NBTHK was uncertain about one character and “quoted” it via an empty box that serves as a placeholder. Next, I would like to contrast the certificate with the actual inscription.

The cutting test inscription is executed in the so-called clerical script ( reisho , ??) which allows a certain amount of freedom in writing and thus there remains some ambiguity and the explanations given in the following represent the interpretation as of today and may be subject to correction in the future.

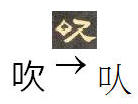

First of all, the third character is quoted in the NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon certificate as (?) which means “blow (wind, etc.), whistle, play an instrument” and which does not make sense in the cutting test (at least not at the position in the “sentence” as at another position, it may be interpreted as “cutting through a target as swiftly as the wind blows”). In my opinion, the reisho character in question is (?), which is a variant of the character (?), having the meaning “with, by, by means of, using.” This character now would be compatible with the notation of the inscription in classical Chinese ( kanbun ), meaning: “Using (?) a criminal (??) for the test cut (?) on the testing grounds (??)…”

The next questionable character is the one preceding the empty box placeholder. The NBTHK quotes the character as ( ? ), waki

, which is often seen on cutting tests referring to the so-called wakige

(??) cut going horizontally through the thorax at the level of the armpits. This character however ends with two (??) radicals at the bottom right whereas the reisho

character seen on the very tang does show the radical ( ? ) at this position. So, in view with the upper part of the right hand side of this character, I am of the opinion that not waki

(?) but sune

(?) is the correct character.

The next questionable character is the one preceding the empty box placeholder. The NBTHK quotes the character as ( ? ), waki

, which is often seen on cutting tests referring to the so-called wakige

(??) cut going horizontally through the thorax at the level of the armpits. This character however ends with two (??) radicals at the bottom right whereas the reisho

character seen on the very tang does show the radical ( ? ) at this position. So, in view with the upper part of the right hand side of this character, I am of the opinion that not waki

(?) but sune

(?) is the correct character.

This brings us the character that the NBTHK did not quote at (i.e. state with the box placeholder) all but which is in my opinion the character (?). This character means literally “Ah!” or “indeed” but has in my opinion here an emphasizing meaning, i.e. “with ease” (see suggested translation below).

This brings us the character that the NBTHK did not quote at (i.e. state with the box placeholder) all but which is in my opinion the character (?). This character means literally “Ah!” or “indeed” but has in my opinion here an emphasizing meaning, i.e. “with ease” (see suggested translation below).

Last but not least, the third-last character, which is quoted in the Tokubetsu Hozon

certificate as (?) but which I think is actually (?). Fugen

(??) is a concrete term whereas (??) is not (but which would read fukan

). Fugen

namely means “no decrease, unabsorbed, undamped” whereas (??) would mean literally “no frontier, no boundary.”

Last but not least, the third-last character, which is quoted in the Tokubetsu Hozon

certificate as (?) but which I think is actually (?). Fugen

(??) is a concrete term whereas (??) is not (but which would read fukan

). Fugen

namely means “no decrease, unabsorbed, undamped” whereas (??) would mean literally “no frontier, no boundary.”

With this, I arrive – for the time being and with the suggestion for the correction of the first addressed character as the most uncertain – for the time being at the following reading of the cutting test:

With this, I arrive – for the time being and with the suggestion for the correction of the first addressed character as the most uncertain – for the time being at the following reading of the cutting test:

- ????????????????

- Tameshiba keijin-giri o motte tachi-kesa oyobi sune kyo fugen Sen’a

- “Sen’a tested this blade on a criminal and cut through a body via the standing

- kesa [diagonal across the body] cut and with ease down to the [height of the] shin.”

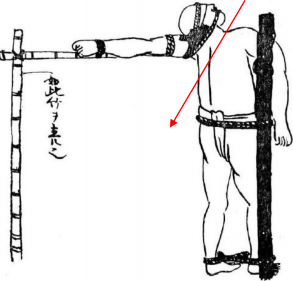

The kesa

cut would go diagonally from the right shoulder down to the left side of the body. When we now assume that not that very set up was used for the cut (sword testers were able to take certain liberties in the set up of the tests as these were not set in stone) but the one for the so- called “walking kesa

cut” ( aruki-kesa

), it is conceivable that after the blade went diagonally through the body it was only stopped by the shin of the criminal.

The kesa

cut would go diagonally from the right shoulder down to the left side of the body. When we now assume that not that very set up was used for the cut (sword testers were able to take certain liberties in the set up of the tests as these were not set in stone) but the one for the so- called “walking kesa

cut” ( aruki-kesa

), it is conceivable that after the blade went diagonally through the body it was only stopped by the shin of the criminal.

Now back to cutting tests in general. In terms of rarity, it is estimated that less than 5% of all blades currently existing were used for cutting test purposes on human corpses. Cutting tests were basically subdivided into hitotsu-d?

(???) and kasane-d?

(???), the former category applying to all cuts carried out on a single body and the latter on stacked bodies or on bodies arranged next to each other. To state now that a sword has a superior or better-than-average cutting ability, one either uses a demanding hitotsu-d?

or a kasane-d?

setup with as much as possible bodies.

Now back to cutting tests in general. In terms of rarity, it is estimated that less than 5% of all blades currently existing were used for cutting test purposes on human corpses. Cutting tests were basically subdivided into hitotsu-d?

(???) and kasane-d?

(???), the former category applying to all cuts carried out on a single body and the latter on stacked bodies or on bodies arranged next to each other. To state now that a sword has a superior or better-than-average cutting ability, one either uses a demanding hitotsu-d?

or a kasane-d?

setup with as much as possible bodies.

Therefore we find relatively many two body cuts as piling up two torsos was, so to speak, the “entry level” into impressive sounding cutting tests. When we use the data of all blades that passed the NBTHK j?y? and tokubetsu-j?y? criteria, we arrive at the following statistics: Of roughly 14,000 blades in total, only about 130 bear a cutting test, what equals to about 1%. Of course, this data is very limited but it offers the only concrete data base to work with for the time being. Of these 120 cutting tests swords about 80 (?) cut through two bodies, about 40 (?) through three bodies, and only two blades are registered that cut through four bodies. However, we know blades that cut through five, six, and even up to seven bodies from outside the realm of j?y? and tokubetsu-j?y? swords (see Sesko, Tameshigiri – The History and Development of Japanese Sword Testing , p. 186ff) but these are considered as an absolute rarity.

Speaking of rarity, from among the about 130 cutting test blades that passed j?y? and tokubetsu-j?y? , only three show a reference to a kesa cut and one of its variants.

Article © 2020 Markus Sesko & samuraisword.com / Tim Pepin

Article content and imagery may not be copied, reproduced in part or whole without our express permission.

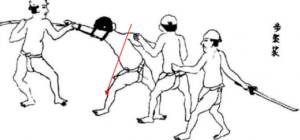

“A depiction of shinnin-tameshi (standard cutting test) being performed.”

Image courtesy of Markus Sesko “Tameshigiri”, The History and Development of Japanese Sword Testing

This Sword is not available for purchase.

If you wish to purchase a Japanese Sword, please view our Nihonto for sale page or contact us directly via email or by telephone at 1(608) 315-0083 any time. Please include specifics of what you seek, i.e.: Katana, maker, era, price range, etc.

Pictures and content may not be copied without the express permission of samuraisword.com ©